Rotator cuff tears

A rotator cuff tear is a common cause of pain and disability among adults. Each year, almost 2 million people in the United States visit their doctors because of a rotator cuff problem.

Rotator cuff tears remain one of the most common causes of shoulder pain and disability among adults. In fact, by the time one reaches the age of 60, there is a 50% chance of at least a partial tear of the rotator cuff. For those fortunate enough to have a painful rotator cuff tear, there is a 50% chance of having a silent rotator cuff tear in the other shoulder!

There are four tendons that make up the rotator cuff; however, the vast majority of tears occur in the supraspinatus tendon. With rare exceptions, tears of the supraspinatus occur at the attachment to the bone.

A torn rotator cuff will weaken your shoulder. This means that many daily activities, like combing your hair or getting dressed, may become painful and difficult to do.

Your shoulder is made up of three bones: your upper arm bone (humerus), your shoulder blade (scapula), and your collarbone (clavicle). The shoulder is a ball-and-socket joint: the ball, or head, of your upper arm bone fits into a shallow socket in your shoulder blade.

When one or more of the rotator cuff tendons is torn, the tendon no longer fully attaches to the head of the humerus.

Most tears occur in the supraspinatus tendon, but other parts of the rotator cuff may also be involved.

In many cases, torn tendons begin by fraying. As the damage progresses, the tendon can completely tear, sometimes with lifting a heavy object.

There are different types of tears:

- Partial tear. This type of tear is also called an incomplete tear. It damages the tendon but does not completely sever it.

- Full-thickness tear. This type of tear is also called a complete tear. It separates all of the tendon from the bone. With a full-thickness tear, there is basically a hole in the tendon.

Cause

There are two main causes of rotator cuff tears: injury and degeneration.

Acute Tear

If you fall down on your outstretched arm or lift something too heavy with a jerking motion, you can tear your rotator cuff. This type of tear can occur with other shoulder injuries, such as a broken collarbone or dislocated shoulder.

Degenerative Tear

There are many causes of rotator cuff tears. Most commonly, degeneration of the rotator cuff and normal aging results in a weak tendon that can easily tear. Often, the patient cannot recall a specific event that may have caused the tear. In other cases, a specific event can be identified.

When a rotator cuff tears, the shoulder becomes painful and often weak. Pain often radiates down the arm in the region of the deltoid muscle. Shoulder motion may be lost. It may be difficult to sleep at night and to use the affected arm during the day.

Most tears are the result of a wearing down of the tendon that occurs slowly over time. This degeneration naturally occurs as we age. Rotator cuff tears are more common in the dominant arm. If you have a degenerative tear in one shoulder, there is a greater likelihood of a rotator cuff tear in the opposite shoulder — even if you have no pain in that shoulder.

Several factors contribute to degenerative, or chronic, rotator cuff tears.

- Repetitive stress. Repeating the same shoulder motions again and again can stress your rotator cuff muscles and tendons. Baseball, tennis, rowing, and weightlifting are examples of sports activities that can put you at risk for overuse tears. Many jobs and routine chores can cause overuse tears, as well.

- Lack of blood supply. As we get older, the blood supply in our rotator cuff tendons lessens. Without a good blood supply, the body’s natural ability to repair tendon damage is impaired. This can ultimately lead to a tendon tear.

- Bone spurs. As we age, bone spurs (bone overgrowth) often develop on the underside of the acromion bone. When we lift our arms, the spurs rub on the rotator cuff tendon. This condition is called shoulder impingement, and over time will weaken the tendon and make it more likely to tear.

The most common symptoms of a rotator cuff tear include:

- Pain at rest and at night, particularly if lying on the affected shoulder

- Pain when lifting and lowering your arm or with specific movements

- Weakness when lifting or rotating your arm

- Crepitus or crackling sensation when moving your shoulder in certain positions

Tears that happen suddenly, such as from a fall, usually cause intense pain. There may be a snapping sensation and immediate weakness in your upper arm.

Tears that develop slowly due to overuse also cause pain and arm weakness. You may have pain in the shoulder when you lift your arm, or pain that moves down your arm. At first, the pain may be mild and only present when lifting your arm over your head, such as reaching into a cupboard. Over-the-counter medication, such as aspirin or ibuprofen, may relieve the pain at first.

Over time, the pain may become more noticeable at rest, and no longer goes away with medications. You may have pain when you lie on the painful side at night. The pain and weakness in the shoulder may make routine activities such as combing your hair or reaching behind your back more difficult.

It should be noted that some rotator cuff tears are not painful. These tears, however, may still result in arm weakness and other symptoms.

Examination and Imaging

Clinical findings of rotator cuff tears include signs of mechanical impingement and weakness of the rotator cuff. This can be tested by abducting the arm to shoulder level, bending the elbow, and rotating the forearm internally and externally (Hawkins Test). Pain during this maneuver is consistent with impingement. Alternatively, impingement can be tested by simply elevating the arm above shoulder level (Neer Test). To isolate the supraspinatus, the arm is placed at shoulder level with the elbow extended and the thumb pointing down (internal rotation). Weakness during isolated supraspinatus testing is consistent with a tear of the supraspinatus.

Other tests which may help Prof Imam or a member of the team confirm your diagnosis include:

- X-rays. The first imaging tests performed are usually x-rays. Because x-rays do not show the soft tissues of your shoulder like the rotator cuff, plain x-rays of a shoulder with rotator cuff pain are usually normal or may show a small bone spur.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or ultrasound. These studies can better show soft tissues like the rotator cuff tendons. They can show the rotator cuff tear, as well as where the tear is located within the tendon and the size of the tear. An MRI can also give Prof Imam a better idea of how “old” or “new” a tear is because it can show the quality of the rotator cuff muscles.

Treatment

If you have a rotator cuff tear and you keep using it despite increasing pain, you may cause further damage. A rotator cuff tear can get larger over time.

Chronic shoulder and arm pain are good reasons to see us. Early treatment can prevent your symptoms from getting worse. It will also get you back to your normal routine that much quicker.

The goal of any treatment is to reduce pain and restore function. There are several treatment options for a rotator cuff tear, and the best option is different for every person. In planning your treatment, Prof Imam or a member of the team will consider your age, activity level, general health, and the type of tear you have.

Non-operative management of rotator cuff tears consists of a combination of activity modification, physical therapy, anti-inflammatory medications, and cortisone injections. Studies in the orthopaedic literature have noted that non-operative treatment will help in approximately 60 to 70% of patients.

It is therefore often the initial recommendation for patients with minimal demands on their shoulders. Patients with higher demands on their shoulders should be strongly considered for early operative treatment. The best results of rotator cuff repairs are in patients treated early.

Surgical Treatment

Prof Imam may recommend surgery if your pain does not improve with nonsurgical methods. Continued pain is the main indication for surgery. If you are very active and use your arms for overhead work or sports, Prof Imam may also suggest surgery.

Surgical treatment of rotator cuff tears involves repairing the rotator cuff to the greater tuberosity where it normally inserts. This section of the greater tuberosity is called the “footprint” of the rotator cuff. Historically, this surgery was performed using a large incision over the shoulder, and often required a temporary detachment of a portion of the deltoid.

With the advancement of arthroscopic surgery, even the largest of rotator cuff tears are now being treated using an all-arthroscopic minimally invasive technique. Most of the recent technological advancements in rotator cuff surgery have been directed at re-attaching the rotator cuff back to the anatomic position where it was torn, completely covering the “footprint” of the rotator cuff.

Several biomechanical studies have concluded that the strongest repair of the rotator cuff is achieved by using a double row method. Double row repairs of the rotator cuff involve placing two sets of attachment on either side of the rotator cuff tendon edge (see figures to right). The sutures repairing the rotator cuff create a web of compression over the tendon, creating the best environment for healing.

Results of rotator cuff repairs continue to improve, as technological advancements facilitate arthroscopic repairs of rotator cuff tears of all sizes. With an emphasis on recreating normal anatomical attachment of the rotator cuff, all-arthroscopic double row rotator cuff repairs remain on the cutting edge of shoulder surgery.

Other signs that surgery may be a good option for you include:

- Your symptoms have lasted 6 to 12 months

- You have a large tear (more than 3 cm) and the quality of the surrounding tissue is good

- You have significant weakness and loss of function in your shoulder

- Your tear was caused by a recent, acute injury

Surgery to repair a torn rotator cuff most often involves re-attaching the tendon to the head of humerus (upper arm bone). There are a few options for repairing rotator cuff tears. Prof Imam will discuss with you the best procedure to meet your individual health needs.

Augmentation (Supportive repair)

The REGENETEN Bioinductive Implant, comprised of type 1 collagen, is an advanced healing solution for biological enhancement and tendon regeneration across all rotator cuff tear types.

As a different approach to managing rotator cuff pathology, evidence has demonstrated:

- Clinical performance in partial-thickness, large, and massive tears

- Repair strength in the induced tissue, not the implant, and completely absorbed within six months

- Increased and sustained tendon thickness, observed up to 5 years

- Improved patient satisfaction, pain, and recovery. (Read more)

Recovery

Pain Management

After surgery, you will feel pain. This is a natural part of the healing process. Our team and nurses will work to reduce your pain, which can help you recover from surgery faster.

Medications are often prescribed for short-term pain relief after surgery. Many types of medicines are available to help manage pain, including opioids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and local anesthetics. Prof Imam or one of our anaesthetists may use a combination of these medications to improve pain relief, as well as minimize the need for opioids.

Be aware that although opioids help relieve pain after surgery, they are a narcotic and can be addictive. Opioid dependency and overdose has become a critical public health issue. It is important to use opioids only as directed by Prof Imam. As soon as your pain begins to improve, stop taking opioids. Talk to if your pain has not begun to improve within a few weeks after your surgery.

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation plays a vital role in getting you back to your daily activities. A physical therapy program will help you regain shoulder strength and motion.

Immobilization. After surgery, therapy progresses in stages. At first, the repair needs to be protected while the tendon heals. To keep your arm from moving, you will most likely use a sling and avoid using your arm for the first 4 to 6 weeks. How long you require a sling depends upon the severity of your injury.

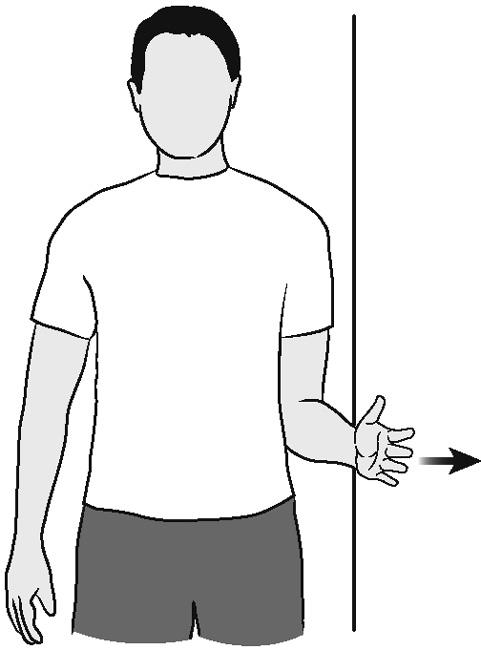

Active exercise during rehabilitation may include isometic external rotation exercises, such as the one shown here.

Passive exercise. Even though your tear has been repaired, the muscles around your arm remain weak. Once your surgeon decides it is safe for you to move your arm and shoulder, a therapist will help you with passive exercises to improve range of motion in your shoulder. With passive exercise, your therapist supports your arm and moves it in different positions. In most cases, passive exercise is begun within the first 4 to 6 weeks after surgery.

Active exercise. After 4 to 6 weeks, you will progress to doing active exercises without the help of your therapist. Moving your muscles on your own will gradually increase your strength and improve your arm control. At 8 to 12 weeks, your therapist will start you on a strengthening exercise program.

Expect a complete recovery to take several months. Most patients have a functional range of motion and adequate strength by 4 to 6 months after surgery. Although it is a slow process, your commitment to rehabilitation is key to a successful outcome.

Outcome

The majority of patients report improved shoulder strength and less pain after surgery for a torn rotator cuff.

Each surgical repair technique (open, mini-open, and arthroscopic) has similar results in terms of pain relief, improvement in strength and function, and patient satisfaction. Surgeon expertise is more important in achieving satisfactory results than the choice of technique.

Factors that can decrease the likelihood of a satisfactory result include:

- Poor tendon/tissue quality

- Large or massive tears

- Poor patient compliance with rehabilitation and restrictions after surgery

- Patient age (older than 65 years)

- Smoking and use of other nicotine products

- Workers’ compensation claims

Complications

After rotator cuff surgery, a small percentage of patients experience complications. In addition to the risks of surgery in general, such as blood loss or problems related to anesthesia, complications of rotator cuff surgery may include:

- Nerve injury. This typically involves the nerve that activates your shoulder muscle (deltoid).

- Infection. Patients are given antibiotics during the procedure to lessen the risk for infection. If an infection develops, an additional surgery or prolonged antibiotic treatment may be needed.

- Deltoid detachment. In the case of an open repair, this shoulder muscle is detached to provide better access to the rotator cuff. It is stitched back into place at the end of the procedure. It is very important to protect this area after surgery and during rehabilitation to allow it to heal.

- Stiffness. Early rehabilitation lessens the likelihood of permanent stiffness or loss of motion. Most of the time, stiffness will improve with more aggressive therapy and exercise.

- Tendon re-tear. There is a chance for re-tear following all types of repairs. The larger the tear, the higher the risk of re-tear. Patients who re-tear their tendons usually do not have greater pain or decreased shoulder function. Repeat surgery is needed only if there is severe pain or loss of function

- Three-Year Functional Outcome of Transosseous-Equivalent Double-Row vs Single-Row Repair of Small and Large Rotator Cuff Tears. A Double-Blinded Randomized Controlled Trial

- Clinical and radiological outcome of rotator cuff repair using all suture anchors.

- Hamburger Technique: Augmented Rotator Cuff Repair With Biological Superior Capsular Reconstruction. Double versus Single row rotator cuff repairs; a double-blinded RCT

- Degenerative rotator cuff tear, repair or not repair? A review of current evidence.

- The X-Pulley Technique for Subpectoral Long Head of the Biceps Tenodesis Using All-Suture Anchors.

- Outcomes following arthroscopic transosseous equivalent suture bridge double-row rotator cuff repair: a prospective study and short-term results.

- What do patients expect of rotator cuff repair and does it matter

- The “Pull-Over” Technique for All Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair With Extracellular Matrix augmentation

- Patient expectations after arthroscopic shoulder surgery

- Clinical Applications of Expanded stem cells in managing tendons pathology

- Superior Capsule Reconstruction for Irreparable Rotator cuff tears; what do we know?

- Is inpatient stay following arthroscopic rotator-cuff repair determined by whether the patient undergoes surgery in the morning or afternoon?